| Sale of

Principal Residence You may avoid tax on gain on the sale of a

principal residence if you owned and used it for at least two years during

the five-year period ending on the date of sale. If you are single, you may

avoid tax on up to $250,000 of gain, $500,000 if you are married and file

jointly. However, gain attributable to nonqualified use after 2008 is not

excludable.

If you used the residence for less than two years, you may avoid tax if you

sold because of a change of job location, poor health or unforeseen

circumstance.

You may not deduct a loss on the sale of a personal residence. Losses on the

sale of property devoted to personal use are nondeductible. However,

there are circumstances under which you may claim a loss deduction on the

sale of a residence.

If you rent out a residential property and you or family members also use

the residence during the year, rental expenses are subject to special

restrictions.

Avoiding Tax on Sale of Principal Residence

If you sell (or exchange) your principal residence at a gain, up to

$250,000 of the gain may be excluded from income if you owned and occupied

it as a principal residence for an aggregate of at least two years in the

five-year period ending on the date of sale and did not claim an exclusion

on another sale within the prior two years. See the discussion of the

two-out-of-five-year ownership and use tests in the following section. If you are married filing jointly, you may be able to exclude up to

$500,000 of gain. Even if you do not meet the two-out-of-five-year

ownership and use tests, you are entitled to a reduced maximum exclusion

limit if the primary reason for your sale was a change in the place of

employment, health reasons, or unforeseen circumstances.

Filing Instruction

Reporting Home Sale Gain or Loss on Your Return

If you have a gain on the sale of your principal residence and the entire

gain is excludable from income under the rules discussed in this topic, you

do not have to report the sale at all on your return unless you received a

Form 1099-S from the settlement agent reporting the sale. If you have a

taxable gain and did not receive Form 1099-S, or you received Form 1099-S

and have any gain that cannot be excluded, or you decide not to claim the

exclusion for excludable gain, report the transaction on Form 8949. If you

can exclude all or part of your gain, you claim the allowable exclusion by

entering code “H” in column (f) of Form 8949 and entering the exclusion as a

negative adjustment in column (g).

If you have gain that cannot be excluded,the taxable gain is subject to the

3.8% Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT), provided your income exceeds the

applicable threshold for the NIIT.

If you had a loss on the sale of your home, the loss is not deductible, but

if you received a Form 1099-S, you must report the sale on Form 8949.

Caution: If you use a residence as a vacation home or rental property after

2008, an allocable part of your gain may not qualify for the exclusion, even

if you meet the two-out-of-five-year ownership and use tests.

Frequency of exclusion. If you meet the ownership and use tests for a

principal residence, you may claim the exclusion when you sell it

although you previously claimed the exclusion for another residence,

provided that the sales are more than two years apart. If you claim the

exclusion on a sale and within two years of the first sale you sell another

principal residence, an exclusion may not be claimed on the second sale even

if you meet the ownership and use tests for that residence. There is an

exception if the second sale was due to a change in employment, health

reasons, or unforeseen circumstances. In that case, a prorated exclusion

limit is allowed.

Planning Reminder

Form 1099-S

The settlement agent responsible for closing the sale of your principal

residence must report the sale to the IRS on Form 1099-S if the sales price

exceeded $250,000, or $500,000 if you are married filing jointly. If the

price was $250,000/$500,000 or less and you provide a written, signed

certification that the full amount of your gain qualifies for the exclusion,

the settlement agent may rely on the certification and not file the Form

1099-S or may choose to file the form anyway. IRS Revenue Procedure 2007-12

has a sample certification form, but certain required assurances that are

not included in Revenue Procedure 2007-12 must be added to your

certification; see the Form 1099-S instructions .

Principal residence. A principal residence is not restricted to

one-family houses but includes a mobile home, trailer, houseboat, and

condominium apartment used as a principal residence. An investment in a

retirement community does not qualify as a principal residence unless you

receive equity in the property. In the case of a tenant-stockholder of a

cooperative housing corporation, the residence ownership requirement applies

to the ownership of the stock and the use requirement applies to the house

or apartment that the stockholder occupies.

If you have multiple homes. If you have more than one home, you may exclude

gain only on the sale of your principal residence and only if you meet the

ownership and use tests for that residence. Your “principal

residence” is determined on a year-to-year basis, based primarily on where

you live most of the time. However, the IRS may also consider such factors

as the primary residence of your family members, your place of employment,

mailing address, the address listed on your tax returns, driver’s license

and automobile and voter registration, and the location of your bank.

Vacant land. Vacant land owned and used as part of a taxpayer’s principal

residence may qualify for the exclusion. The vacant land must be adjacent to

the residence and the sale of the residence must be within two years before

or after the sale of the land. Qualifying sales of land and residence are

treated as one sale, so the $250,000 exclusion limit ($500,000 for

qualifying joint filers) applies to the combined sales. If the sales occur

in different years, the exclusion limit applies first to the residence sale.

Business or rental use. If part of your home was rented out or used for

business, see the rules for determining whether you can exclude all or some

of the gain on a sale. Also see the rules for deducting a loss where

your residence was converted to rental property.

Home destroyed or condemned. If your home is destroyed or condemned, this is

treated as a sale, so any gain realized on the conversion may qualify for

the exclusion. If vacant land used as part of your home is sold within two

years of the conversion, the sale of the land may be combined with the sale

of the residence for exclusion purposes.

Any part of the gain that may not be excluded (because it exceeds the limit)

may be postponed under the rules.

Sale of remainder interest. You may choose to exclude gain from the sale of

a remainder interest in your home. If you do, you may not choose to exclude

gain from your sale of any other interest in the home that you sell

separately. Also, you may not exclude gain from the sale of a remainder

interest to a related party. Related parties include your brothers and

sisters, half-brothers and half-sisters, spouse, ancestors (parents,

grandparents, etc.), and lineal descendents (children, grandchildren, etc.).

Related parties also include certain corporations, partnerships, trusts, and

exempt organizations.

Expatriates. You cannot claim the home sale exclusion if the expatriation

tax applies to you. The expatriation tax applies to U.S. citizens who

have renounced their citizenship (and long-term residents who have ended

their residency) if one of their principal purposes was to avoid U.S. taxes.

The exclusion is not mandatory. You do not have to apply the exclusion to a

particular qualifying sale. For example, you are unable to sell a residence

when you acquire a new residence. When you finally are able to find a buyer

for the first home, you also decide to sell the second residence. Assume

both sales may qualify for the exclusion, but the potential gain on the

first house will be less than the potential gain on the sale of the second

home. You will not want to apply the exclusion to the sale of the first home

if doing so will prevent you from applying the exclusion to the second sale

because of the rule allowing an exclusion for only one sale every two years.

Federal subsidy recapture. If your home was financed with the proceeds of a

tax-exempt bond or a qualified mortgage credit certificate and you

sell or dispose of the home within nine years of the financing, you may have

to recapture the federal subsidy received even if the sale qualifies for the

home sale exclusion. Use Form 8828 to figure the amount of the recapture

tax, which is reported on Form 1040 as a separate tax.

Meeting the Ownership and Use Tests for Exclusion

To qualify for the up-to-$250,000 exclusion, you must have owned and

occupied a home as your principal residence for at least two years during

the five-year period ending on the date of sale. The periods of ownership

and use do not have to be continuous. The ownership and use tests may be met

in different two-year periods, provided both tests are met during the

five-year period ending on the date of sale (as in Example 3 below). You

qualify if you can show that you owned the home and lived in it as your

principal residence for 24 full months or for 730 days (365 × 2) during the

five-year period ending on the date of sale. However, even you meet the

two-out-of-five-year ownership and use tests, some of your gain will be

taxable if you use the residence after 2008 as a second home or rental

property, unless an exception applies; see the discussion of the

nonqualified use rule at the end of this section.

If you or your spouse serve on qualified official extended duty as a member

of the uniformed services, Foreign Service of the United States,

intelligence community, or Peace Corps, you can suspend the five-year test

period for the years of qualified service.

Filing Tip

Short Absences

Short temporary absences for vacations count as time you used the residence.

If you are a joint owner of the residence and file a separate return, the

up-to-$250,000 exclusions applies to your share of the gain, assuming you

meet the ownership and use tests.

If you are married and file a joint return, you may claim an exclusion of up

to $500,000 if one of you meets the ownership test and both of you meet the

use test.

If the ownership and use tests are not met but the primary reason for the

sale was a change in the place of employment, health reasons, or unforeseen

circumstances, an exclusion is allowed under the reduced maximum exclusion

rules.

Even if the ownership and use tests are met, the exclusion is not allowed

for a sale if within the two-year period ending on the date of sale, you

sold another principal residence for which you claimed the exclusion.

However, a reduced exclusion limit may be available.

Court Decision

Use Test Must be Met for Newly Built Home Replacing Demolished Home

If a new house is built on the site of a former residence, the period of use

of the old house does not count towards meeting the two-year use test for

the new house. A couple wanted to remodel their home but, because of

building code and permit restrictions, decided to demolish the old house and

build a new one on the site. Once the new house was completed, they sold it

for $1.1 million, which resulted in a $600,000 gain. On their joint return,

they excluded $500,000 of the gain from their income. They had lived in the

demolished home for a number of years but never lived in the newly

constructed home.

The Tax Court agreed with the IRS that they did not qualify for the

exclusion. The exclusion applies only if the dwelling sold was actually used

by the taxpayer as a principal residence for the required two-out-of-five

years before the sale. In this case, while the demolished home was used as a

principal residence for the requisite period, the newly built home was not.

EXAMPLES

1.

From 2002 through August 2016, Janet lived with her parents in a house that

her parents owned. In September 2016, she bought this house from her

parents. She continued to live there until December 18, 2017, when she sold

it at a gain. Although Janet lived in the home for more than two years, she

did not own it for at least two years. She may not exclude any part of her

gain on the sale, unless she sold because of a change in her place of

employment, health reasons, or unforeseen circumstances.

2. John bought and moved into a house on July 9, 2015. He lived in it as his

principal residence continuously until October 1, 2016, when he went abroad

for a one-year sabbatical leave. After returning from the leave, he sold the

house on November 6, 2017. He does not meet the two-year use test. Because

his sabbatical was not a short, temporary absence, he may not include the

period of leave in his period of use in order to meet the two-year use test.

He may avoid tax on gain if he sold because of a changed job location

unforeseen circumstances, or poor health.

3.

Since 1991, Jonah lived in an apartment building that was changed to a

condominium. He bought the apartment on December 3, 2013. In February 2015,

he became ill and on April 16, 2015, he moved into his son’s home. On July

14, 2017, while still living with his son, he sold the apartment.

He may exclude gain on the sale of the apartment because he met the

ownership and use tests. The five-year period is from July 15, 2012, to July

14, 2017, the date of the sale of the apartment. He owned the apartment from

December 3, 2013, to July 14, 2017 (over two years). He lived in the

apartment from July 15, 2012 (the beginning of the five-year period) to

April 16, 2015, a period of use of over two years.

4.

In 2005, Carol bought a house and lived in it until January 31, 2014, when

she moved and put it up for rent. The house was rented from March 1, 2014,

until May 31, 2017. Carol moved back into the house on June 1, 2017, and

lived there until she sold it on September 30, 2017. During the five-year

period ending on the date of the sale (October 1, 2012 – September 30,

2017), Carol lived in the house for less than two years.

|

Five-year period -- |

Home use (months) -- |

Rental use (months)

-- |

| 10/1/12 - 1/31/14 |

16 |

|

| 3/1/14 - 5/31/17 |

|

39 |

| 6/1/17 - 9/30/17 |

4 |

-- |

| Total |

20 |

39 |

Carol may not exclude any of the gain on the sale, unless she sold the house

for health or employment reasons or due to unforeseen circumstances.

Military and Foreign Service personnel, intelligence officers, and Peace

Corps workers can suspend five-year period. You may elect to suspend the

running of the five-year ownership and use period while you or your spouse

is on qualified official extended duty as a member of the uniformed services

or Foreign Service of the United States. The suspension can be for up to 10

years. It is allowed for only one residence at a time. By making the

election and disregarding up to 10 years of qualifying service, you can

claim an exclusion where the two-year use test is met before you began the

qualifying service and after your return; see the Example below. Qualified

official extended duty means active duty for over 90 days or for an

indefinite period with a branch of the U.S. Armed Forces at a duty station

at least 50 miles from your principal residence or in Government-mandated

quarters. Members of the Foreign Service, commissioned corps of the National

Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and commissioned corps of the Public

Health Service who meet the active duty tests also qualify.

Caution

Residence Acquired in Like-Kind Exchange

A residence acquired in a like-kind exchange must be owned for at least five

years before gain on its sale can qualify for the exclusion.

Court Decision

Co-Owner Can Claim Full $250,000 Exclusion

A single taxpayer who sells her home at a gain after owning and using it for

at least two of the five years preceding the date of sale can exclude up to

$250,000 of gain from income. What if there are two co-owners: do they have

to split the $250,000 exclusion? Yes, argued the IRS in a 2010 case, the

$250,000 exclusion has to be shared, but the Tax Court allowed a full

exclusion. The taxpayer owned a 50% interest in a home she used as her

principal residence since February 1997. When the home was sold in 2005, her

share of the gain was $264,644.50 (half of the $529,289 total gain). She

excluded $250,000 of her gain on her 2005 return, but the IRS said she was

only entitled to half of the full exclusion, or $125,000.

The Tax Court allowed the full $250,000 exclusion. The statute (Code Section

121) does not limit the exclusion for partial owners of a principal

residence. In fact, an example in the IRS regulations specifically allows

unmarried joint owners holding 50% interests in a home to each exclude up to

the full $250,000 limit for their shares of the gain on a sale so long as

they each meet the ownership and use tests and have not excluded gain from

another home sale within the prior two-year period.

Similarly, the five-year testing period is suspended for up to 10 years for

intelligence community employees (specified national agencies and

departments) and Peace Corps workers. The suspension rule for Peace Corps

workers applies to Peace Corps employees, enrolled volunteers, or volunteer

leaders for periods during which they are on qualified official extended

duty outside the United States.

EXAMPLE

Michael bought a home in Maryland in March 2004 that he lived in before

moving to Brazil in November 2008 as a member of the Foreign Service of the

United States. He served there on qualified official extended duty for eight

years, until the end of 2016. In January 2017, he sells the Maryland home at

a gain. He did not use the home as his principal residence for two out of

the five years preceding the sale and so does not qualify for an exclusion

under the regular rule. However, Michael can exclude gain of up to $250,000

by electing to suspend the running of the five-year test period while he was

abroad with the Foreign Service. Under the election, his eight years of

service are disregarded and his years of use from March 2004—November 2008

are considered to be within the five-year period preceding the sale. He thus

meets the two-out-of-five-year test and can claim the exclusion.

Cooperative apartments. If you sell your stock in a cooperative housing

corporation, you meet the ownership and use tests if, during the five-year

period ending on the date of sale, you:

1.

Owned stock for at least two years, and

2.

Used the house or apartment that the stock entitles you to occupy as your

principal residence for at least two years.

Incapacitated homeowner. A homeowner who becomes physically or mentally

incapable of self-care is deemed to use a residence as a principal residence

during the time in which the individual owns the residence and resides in a

licensed care facility. For this rule to apply, the homeowner must have

owned and used the residence as a principal residence for an aggregate

period of at least one year during the five years preceding the sale.

If you meet this disability exception, you still have to meet the

two-out-of-five-year ownership test to claim the exclusion.

Previous home destroyed or condemned. For the ownership and use

tests, you may add time you owned and lived in a previous home that was

destroyed or condemned if any part of the basis of the current home sold

depended on the basis of the destroyed or condemned home under the

involuntary conversion rules.

No Exclusion for Nonqualified Use After 2008

Even if the two-out-of-five-year test for an exclusion is met, gain

attributable to “nonqualified” use after 2008 is not eligible for the

exclusion. The primary intent of the rule is apparently to deny an exclusion

for some of the gain realized by taxpayers who convert a vacation home or

rented residence to their principal residence and live in it for a few years

before selling. However, the law as written is broader, generally treating

any period after 2008 in which the home is not used as a principal residence

by you, your spouse, or former spouse as “nonqualified use.” Despite the

broad wording of the law, there are exceptions ( below) that lessen the

potential impact of the nonqualified use rule. In particular, exception 1

allows many home sellers to avoid nonqualified use treatment where they move

out and rent the home before selling it.

Exceptions to nonqualified use. There are exceptions that limit the impact

of the nonqualified use rule. The law specifically exempts the following

from the definition of post-2008 “nonqualified use”: (1) the period after

you, or your spouse, last use the home as your principal residence, so long

as it is within the five years ending on the date of sale; see Example 2

below, (2) temporary absences from the residence, not to exceed two years in

total, due to a change in employment, health reasons (such as time in a

hospital or nursing home), or other unforeseen circumstances to be specified

by the IRS, and (3) periods of up to 10 years (in aggregate) during which

you, or your spouse, are on qualified official extended duty (duty station

at least 50 miles from residence) as a member of the uniformed services, as

a Foreign Service officer, or as an employee of the intelligence community.

The IRS has not released formal guidelines on “nonqualified use,” including

any other possible exceptions, such as whether short-term rental periods

will be disregarded. However, in Publication 523 it takes the position that

where rental or business space is physically part of the living area of your

home, such as a home office or a spare bedroom that you rent out as part of

a bed-and-breakfast business, that use is treated as residential use.

Although the IRS does not specifically say so, such home office or rental

space within the home is apparently not considered “nonqualified use” in

applying the fractional computation below.

Figuring the excludable and nonexcludable gain. To figure the exclusion on a

sale where there is nonqualified use after 2008, the gain equal to post–May

6, 1997 depreciation (allowed or allowable) is taken into account

first. No exclusion is allowed for this depreciation amount; this is

a long-standing rule that is not changed by the nonqualified use

calculation.

After taking into account post-May 6, 1997 depreciation, the portion of the

remaining gain that is allocable to nonqualified use must be figured; this

amount also is not eligible for the exclusion. The allocation is made by

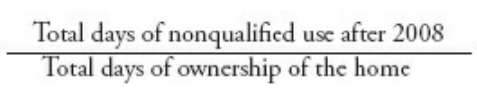

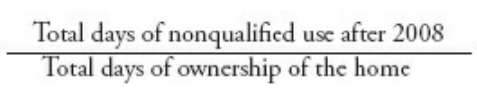

multiplying the gain by the following fraction:

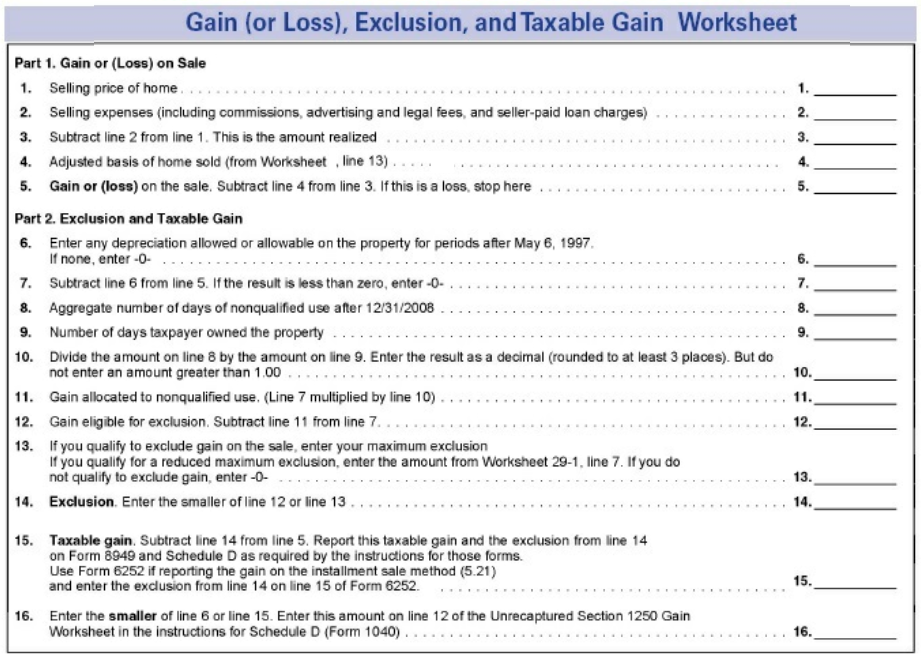

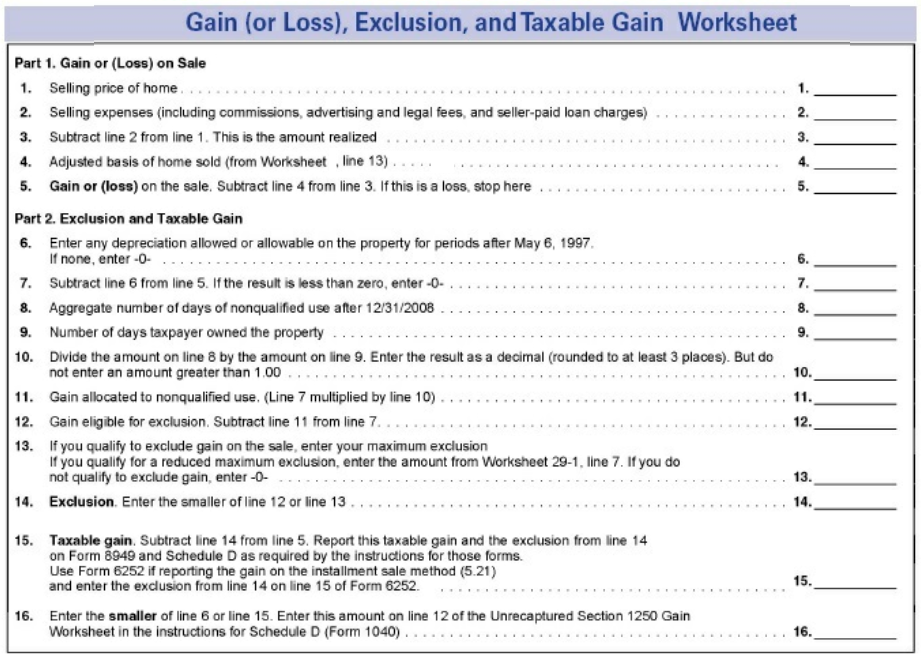

You can use Worksheet 29-3 later in this chapter to make the allocation and

figure your excludable and taxable gain.

EXAMPLES

1.

Martin bought his home on April 23, 2011, and lived in it until June 30,

2013 when he moved out. He rented the home from July 1, 2013, to June 30,

2015, and claimed depreciation deductions of $10,000 for that period. Martin

moved back into the house July 1, 2015, and lived there until he sold it on

January 31, 2017, for a gain of $310,000. In the five-year period ending on

the date of sale (February 1, 2012 – January 31, 2017), Martin met the

ownership and use test for an exclusion: he owned the home and used it for

more than two years in the five-year period. He owned it for the entire five

years and used it as his home for 36 months (17 months from February 1,

2012–June 30, 2013, and 19 months from July 1, 2015–January 31, 2017), while

renting it for the other 24 months (July 1, 2013–June 30, 2015). The rental

period is nonqualified use.

Using the Gain/loss worksheet, Martin figures his exclusion and taxable gain. The

$10,000 of gain allocable to depreciation cannot be excluded. Of the

remaining $300,000 gain ($310,000 gain -$10,000 depreciation), Martin

figures that $103,800 is allocable to nonqualified use and thus not eligible

for an exclusion. Martin owned the home for 2,110 days (beginning with April

24, 2011, the day after he bought it, and ending on January 31, 2017, the

date of sale). Of his 2,110 ownership days, 730 days (the rental days, July

1, 2013 through June 30, 2015) were nonqualified use. The allocation to

nonqualified use is 730/ 2,110, or 34.6%, and 34.6% x $300,000 is $103,800.

Martin may exclude $196,200 of the gain from income ($300,000-$103,800).

On Form 8949 and Schedule D, Martin will report taxable gain of

$113,800 ($10,000 gain allocable to depreciation + $103,800 gain allocable

to nonqualified use), and also will report the exclusion of $196,200. The

$10,000 gain from depreciation is unrecaptured Section 1250 gain, which

Martin will enter on the Unrecaptured Section 1250 Gain Worksheet in the

Schedule D instructions.

Keep in mind that even without the nonqualified use rule, only $250,000 of

Martin’s $300,000 gain (after depreciation is recaptured) would have been

excludable. The effect of the nonqualified use rule under these facts is to

increase the taxed (nonexcludable) gain by an additional $53,800, from

$50,000 ($300,000 – $250,000) to $103,800 under the allocation formula.

2.

Andrea owned and lived in her principal residence from 2011 through 2014 and

then moved to another state. She rented the home from January 1, 2015, until

April 30, 2017, when she sold it. Andrea met the ownership and use test: she

owned and lived in the house for more than two years in the five-year period

ending on the date of sale (May 1, 2012 – April 30, 2017). Although Andrea

rented out the home after 2008, the rental period (January 1, 2015 – April

30, 2017) is not considered nonqualified use because it was after she moved

out of the home and was within the five-year period ending on the sale date

(Exception 1 under “Exceptions to nonqualified use” on the previous page).

Andrea may exclude gain of up to $250,000, but not gain equal to the

depreciation she claimed (or could have claimed) while the house was rented.

Because the property was rented at the time of sale, the IRS requires the

sale to be reported and the exclusion claimed on form 4797.

Home Sales by Married Persons

Where a married couple owned and lived in their principal residence for at

least two years during the five-year period ending on the date of sale, they

may claim an exclusion of up to $500,000 of gain on a joint return. Under

the law, the up-to-$500,000 exclusion may be claimed on a joint return

provided that during the five-year period ending on the date of sale: (1)

either spouse owned the residence for at least two years, (2) both spouses

lived in the house as their principal residence for at least two years, and

(3) neither spouse is ineligible to claim the exclusion because an exclusion

was previously claimed on a sale of a principal residence within the

two-year period ending on the date of this sale. If Tests 1 and 3 are met

but only one of you meets Test 2, your exclusion limit on a joint return is

$250,000. However, even if the two-out-of-five-year use test is met,

“nonqualified use” after 2008 may limit the exclusion you can claim.

Caution

Exclusion for Married Couple

For a recently married couple, the exclusion limit on a joint return is

$250,000, not $500,000, where one of the spouses has satisfied both the

ownership test and the use test before a sale and the other spouse has not

met the use test. Gain in excess of the $250,000 exclusion is reported on

Form 8949.

Death of spouse before sale. If your spouse died and you inherit the house

and later sell it, you are considered to have owned and used the property

during any period of time when your spouse owned and used it as a principal

home, provided you did not remarry before your sale. This rule can enable

you to satisfy the two-out-of-five-year ownership and use tests where your

spouse met the tests but you on your own did not. It may also enable you to

claim the $500,000 exclusion if you sell the house in the year your spouse

died or within the next two years, as discussed in the next two paragraphs.

If you and your spouse each met the use test and at least one of you met the

ownership test as of the date of your spouse’s death, and you sell the

residence in the year he or she dies, you may use the $500,000 exclusion

limit, assuming you file a joint return for the year of your spouse’s death

and neither of you claimed the exclusion for another home sale in the two

years before your spouse died.

You are also entitled to use the $500,000 exclusion limit on a sale that is

within two years of your spouse’s death, provided you have not remarried and

you and your spouse would have qualified for the $500,000 limit on a sale

immediately before his or her death.

EXAMPLES

1.

You and your spouse owned and occupied your principal residence for 20

years. In December 2017, you sell the house for a gain of $450,000. If you

file jointly, none of the gain is taxable as the up-to-$500,000 exclusion

applies.

2.

After your spouse died, you owned and lived in your principal residence from

June 2012 through the end of 2016. In January 2017 you remarried and you and

your wife lived in the house for nine months. In October 2017, you sold the

house and realized a gain of $350,000. On a joint return for 2017, you may

claim an exclusion of $250,000; the balance of $100,000 is taxable. You meet

the exclusion tests, but your wife does not. Thus, the exclusion is limited

to $250,000.

Divorce. If a residence is transferred to you incident to divorce, the time

during which your former spouse owned the residence is added to your period

of ownership. If pursuant to a divorce or separation decree or agreement you

move out of a home that you own or jointly own with your spouse or former

spouse, you are treated as having used the home for any period that you

retain an ownership interest in the residence while the other spouse or

former spouse continues to use it as a principal residence under the terms

of the divorce or separation agreement.

Separate residences. Where a husband and wife own and live in separate

residences, each spouse is entitled to a separate exclusion limit of

$250,000 on the sale of his or her residence. If both residences are sold in

the same year and each spouse met the ownership and use test for his or her

separate residence, two exclusions may be claimed (up to $250,000 each),

either on a joint return or on separate returns.

Reduced Maximum Exclusion

Generally, no exclusion is allowed on a sale of a principal residence if you

owned or used the home for less than two of the five years preceding the

sale. Similarly, an exclusion is generally disallowed if within the

two-year period ending on the date of sale, you sold another home at a gain

that was wholly or partially excluded from your income.

However, even if a sale of a principal residence is made before meeting the

ownership and use tests or it is within two years of a prior sale for which

an exclusion was claimed, a partial exclusion is available if the primary

reason for the sale is: (1) a change in the place of employment, (2) health,

or (3) unforeseen circumstances. If the sale is for one of these qualifying

reasons, you are entitled to a prorated portion of the regular $250,000 or

$500,000 exclusion limit. The employment change, health problem, or

unforeseen circumstance can be attributable to you or another “qualified

individual,” as defined below.

You automatically qualify for the reduced exclusion if your sale is within a

safe harbor established by the IRS. If a safe harbor is not available, you

may qualify by showing that the “facts and circumstances” of your situation

establish that the primary reason for the sale was a change in the place of

employment, health problem or unforeseen circumstances.

When you fall within a safe harbor or meet the primary reason test, you are

allowed an allocable percentage of the regular $250,000 or $500,000

exclusion limit, depending on how much of the regular two-year ownership and

use test was satisfied, or the time between this sale and a sale within the

prior two years. For example, if you owned and lived in your home for 438

days before selling it to take a new job, you are entitled to 60% of the

regular exclusion limit, which is based on 730 qualifying days (438/730 =

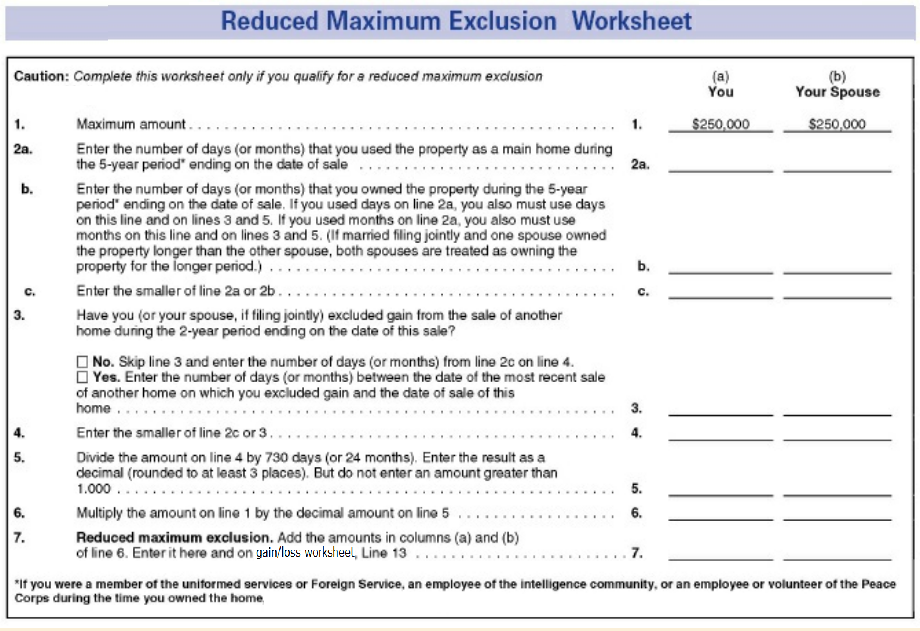

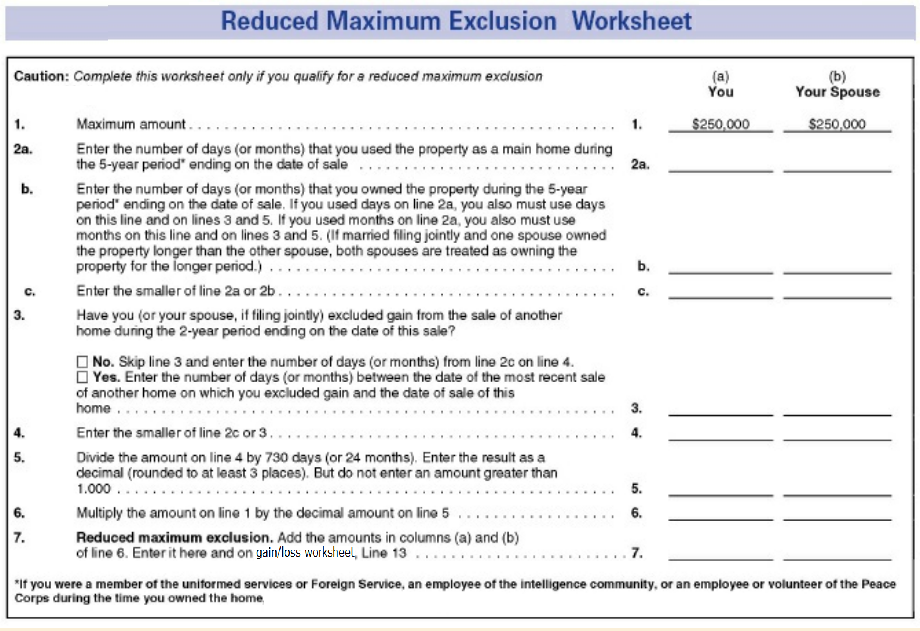

60%). Use the Reduced maximum exclusion worksheet to figure your reduced exclusion limit. Although

the maximum exclusion is reduced, this may not disadvantage you. If the

reduced exclusion limit equals or exceeds your gain, none of your gain is

subject to tax.

IRS Alert

Amended Return to Claim Reduced Maximum Exclusion

If you reported gain on a sale that can be avoided under the reduced maximum

exclusion rules for sales due to a change in place of employment, health, or

unforeseen circumstances, a refund claim can be made on an amended return,

provided the prior year is not closed by the statute of limitations.

Qualified individual. In addition to yourself, the following persons are

considered qualified individuals for purposes of qualifying for the reduced

maximum exclusion: your spouse, a co-owner of the residence, or any person

whose main home was your principal residence.

For purposes of the “health reasons” category, qualified individuals include

not only the above individuals but also their family members: parents or

step-parents, grandparents, children, stepchildren, adopted children,

grandchildren, siblings (including step- or half-siblings), in-laws

(mother/father, brother/sister, son/daughter), uncles, aunts, nephews, or

nieces.

EXAMPLE

You bought and moved into your residence on April 4, 2017, so your holding

period begins on April 5, 2017. In 2018 you move to a new job location in

another state and sell your house at a gain of $50,000 on April 4, 2018.

Since you owned and used your home for 12 months (365 days), your exclusion

limit is reduced by 50% (365/730 days). You are single. Your reduced

exclusion limit is $125,000 (50% of $250,000) and since the gain of $50,000

is totally covered by the $125,000 exclusion it is not taxable.

Sale due to change in place of employment. The reduced exclusion limit

applies if the primary reason for your sale is a change in the location of a

qualified individual’s employment; see the above definition of qualified

individual. “Employment” includes working for the same employer at a

different location or starting with a new employer. It also includes the

commencement of self-employment or the continuation of self-employment at a

new location.

The IRS provides a safe harbor based on distance. If a qualified

individual’s new place of employment is at least 50 miles farther from the

sold home than the old place of employment was, the reduced exclusion limit

is allowed so long as the change in employment occurred while you owned and

used the home as your principal residence. If an unemployed qualified person

obtains employment, the safe harbor applies if the sold home is at least 50

miles from the place of employment.

If the 50-mile safe harbor cannot be met, the facts and circumstances may

indicate that a change in the place of employment was the primary reason for

the sale, thereby allowing the reduced exclusion limit.

EXAMPLE

An emergency room physician buys a condominium in March 2017 that is five

miles from the hospital where she works. In November 2017, she takes a new

job at a hospital 51 miles away from her home. She sells her home in

December 2017 and buys a townhouse that is four miles away from the new

hospital. The sale does not qualify for the 50-mile safe harbor since the

new hospital is only 46 miles further from the old home than the first

hospital was. However, given the doctor’s need to work unscheduled hours and

to get to work quickly, the IRS allows the reduced exclusion limit; the

facts show that her change in place of employment was the primary reason for

the home sale.

Sale due to health problems. The reduced exclusion limit applies if a

principal residence is sold primarily to obtain or facilitate the diagnosis,

treatment, or mitigation of a qualified person’s disease, illness or injury,

or to obtain or provide medical or personal care for a qualified individual

suffering from a disease, illness, or injury. A sale does not qualify if it

is merely to improve general health. Note that for “health sales,” the

definition of qualified individual is broadened to include family members;

see above.

A physician’s recommendation of a change in residence for health reasons

automatically qualifies under an IRS safe harbor.

EXAMPLES

1.

One year after purchasing a home in Michigan, Smith is told by his doctor

that moving to a warm, dry climate would mitigate his chronic asthma

symptoms. Smith takes the advice, selling the house and moving to Arizona.

The sale is within the doctor recommendation safe harbor and Smith may claim

a reduced maximum exclusion for gain on the sale of the Michigan home.

1.

In 2017, Mike and Kathy Anderson sell the house they bought in 2016 so they

can move in with Kathy’s father, who is chronically ill and unable to care

for himself. The IRS allows the Andersons to claim a reduced maximum

exclusion, as the primary reason for the sale is to provide care for Kathy’s

father, a qualified individual.

Sale due to unforeseen circumstances. A sale of a principal residence due to

any of the following events fits within an IRS safe harbor for unforeseen

circumstances and automatically qualifies for a reduced maximum exclusion:

(1) The involuntary conversion of the home (condemnation or destruction of

house in a storm or fire);

(2) Damage to the residence from a natural or man-made disaster, war, or act

of terrorism;

(3) Any of the following events involving a qualified individual: death, divorce or legal separation, becoming eligible for

unemployment compensation, a change in employment or self-employment status

that left the qualified individual unable to pay housing costs and

reasonable basic household expenses, or multiple births resulting from the

same pregnancy.

The IRS may expand the list of safe harbors in generally applicable revenue

rulings or in private rulings requested by individual taxpayers.

Sales not covered by a safe harbor can qualify if the facts and

circumstances indicate that the home was sold primarily because of an event

that could not have been reasonably anticipated before the residence was

purchased and occupied. The IRS in private letter rulings has been quite

liberal in allowing the reduced maximum exclusion for unforeseen sales; see

the examples below. Even the birth of a second child has been held to be an

unforeseen circumstance (Example 5). However, an improvement in financial

circumstances does not qualify under IRS regulations, even if the

improvement is the result of unforeseen events, such as receiving a

promotion and a large salary increase that would allow the purchase of a

bigger home.

EXAMPLES

1.

Three months after Jones buys a condominium as his principal residence, the

condominium association replaces the roof and heating system and a few

months later the monthly condominium fees are doubled. If Jones sells the

condo because he cannot pay the higher fees and his monthly mortgage

payment, the sale is considered to be due to unforeseen circumstances and

Jones may claim a reduced maximum exclusion.

2.

Tom and his fiancée, Alice, buy a house and live in it as their principal

residence. The next year they break up and Tom moves out. The house is sold

because Alice cannot afford to make the monthly payments alone. According to

the IRS, the sale is due to unforeseen circumstances and Alice and Tom may

each claim a reduced maximum exclusion.

3.

A married couple purchased a home in a retirement community that had minimum

age requirements for residents. Shortly after they moved in, their daughter

lost her job and was in the process of getting a divorce. The daughter and

her child wanted to move in but could not because of the community’s age

requirements. The couple sold the home and bought a new one in which their

daughter and grandchild lived while the daughter looked for full-time

employment. The IRS privately ruled that the sale of the retirement

community home was due to unforeseen circumstances and the reduced maximum

exclusion could be claimed.

4.

A single mother bought a home and lived in it with her two daughters as

their principal residence. One of the daughters was subjected to unruly

behavior, verbal abuse, and sexual assault on the school bus. As a result,

the daughter suffered from persistent fear and her school performance

seriously declined. Her behavior was noticed by the school and brought to

the mother’s attention. She tried to work with the school district to

resolve the problem, but when attempts failed, she sold her home and moved.

The mother had not owned the home for two full years and asked the IRS

whether she qualified for a partial exclusion. The IRS said yes. The primary

reason for the sale prior to satisfying the two-year test was an unforeseen

circumstance—the extreme bullying suffered by her daughter. Therefore, she

can prorate the home sale exclusion for the part of the two years that she

owned and lived in the home.

5.

A married couple with one child bought a condominium with two small bed

rooms and two baths. The child’s bedroom was also used as the husband’s home

office and a guest room. After the wife gave birth to a second child, they

moved out of the condo and later sold it at a gain. The IRS in a private

ruling concluded that the birth of a second child was an unforeseen

circumstance that rendered the condo unsuitable as a residence. Therefore,

the couple could claim the reduced maximum exclusion.

Figuring Gain or Loss

To figure the gain or loss on the sale of your principal residence, you must

determine the selling price, the amount realized, and the adjusted basis.

The Gain/Loss Exclusion and Taxable gain worksheet may be used to figure gain or loss on the sale of a principal

residence.

Filing Tip

Form 1099-S

If you received Form 1099-S, Box 2 should show the gross proceeds from the

sale of your home. However, Box 2 does not include the fair market value of

any property other than cash or notes, or any services you received or will

receive. For these, Box 4 will be checked. If the sales price of your home

does not exceed $250,000 or $500,000 (if filing jointly) and you certify to

the person responsible for closing the sale that your entire gain is

excludable from your gross income, that person does not have to report the

sale on Form 1099-S, but may choose to do so.

Gain or loss. The difference between the amount realized and adjusted basis

is your gain or loss. If the amount realized exceeds the adjusted basis, the

difference is a gain that may be excluded. If amount realized is less than

adjusted basis, the difference is a loss. A loss on the sale of your main

home may not be deducted.

Foreclosure or repossession. If your home was foreclosed on or

repossessed, you have a sale.

Selling price. This is the total amount received for your home. It includes

money, all notes, mortgages, or other debts assumed by the buyer as part of

the sale, and the fair market value of any other property or any services

received. The selling price does not include receipts for personal property

sold with your home. Personal property is property that is not a permanent

part of the home, such as furniture, draperies, and lawn equipment.

If your employer pays you for a loss on the sale or for your selling

expenses, do not include the payment as part of the selling price. Include

the payment as wages on Line 7 of Form 1040. (Your employer includes the

payment with the rest of your wages in Box 1 of your Form W-2.)

If you grant an option to buy your home and the option is exercised, add the

amount received for the option to the selling price of your home. If the

option is not exercised, you report the amount as ordinary income in the

year the option expires. Report the amount on Line 21 of Form 1040.

Amount realized. This is the selling price minus selling expenses, including

commissions, advertising fees, legal fees, and loan charges paid by the

seller (e.g., loan placement fees or “points”).

Adjusted basis. This is the cost basis of your home increased by the cost of

improvements and decreased by deducted casualty losses, if any. Cost

basis is generally what you paid for the residence. If you obtained

possession through other means, such as a gift or inheritance, see the

special basis rules for gifts and inheritances.

Seller-paid points. If the person who sold you your residence paid points on

your loan, you may have to reduce your basis in the home by the amount of

the points. If you bought your residence after 1990 but before April 4,

1994, you reduce basis by the points only if you chose to deduct them as

home mortgage interest in the year paid. If you bought the residence after

April 3, 1994, you reduce basis by the points even if you did not deduct the

points.

Filing Tip

Jointly Owned Home

If you and your spouse sell your jointly owned home and file a joint return,

you figure your gain or loss as one taxpayer. If you file separate returns,

each of you must figure your own gain or loss according to your ownership

interest in the home. Your ownership interest is determined by state law.

If you and a joint owner other than your spouse sell your jointly owned

home, each of you must figure your own gain or loss according to your

ownership interest in the home.

Settlement fees or closing costs. When buying your home, you may have to pay

settlement fees or closing costs in addition to the contract price of the

property. You may include in basis fees and closing costs that are for

buying the home. You may not include in your basis the fees and costs of

getting a mortgage loan. Settlement fees also do not include amounts placed

in escrow for the future payment of items such as taxes and insurance.

Examples of the settlement fees or closing costs that you may include in the

basis of your property are: (1) abstract fees (sometimes called abstract of

title fees), (2) charges for installing utility services, (3) legal fees

(including fees for the title search and preparing the sales contract and

deed), (4) recording fees, (5) survey fees, (6) transfer taxes, (7) owner’s

title insurance, and (8) any amounts the seller owes that you agree to pay,

such as certain real estate taxes, back interest, recording or mortgage

fees, charges for improvements or repairs, and sales commissions.

Examples of settlement fees and closing costs not included in your basis

are: (1) fire insurance premiums, (2) rent for occupancy of the home before

closing, (3) charges for utilities or other services relating to occupancy

of the home before closing, (4) any fee or cost that you deducted as a

moving expense before 1994, (5) charges connected with getting a mortgage

loan, such as mortgage insurance premiums (including VA funding fees), loan

assumption fees, cost of a credit report, and fee for an appraisal required

by a lender, and (6) fees for refinancing a mortgage.

Construction. If you contracted to have your residence built on land you

own, your basis is the cost of the land plus the cost of building the home,

including the cost of labor and materials, payments to a contractor,

architect’s fees, building permit charges, utility meter and connection

charges, and legal fees directly connected with building the home.

Caution

Repairs

These maintain your home in good condition but do not add to its value or

prolong its life. You do not add their cost to the basis of your property.

Examples of repairs include repainting your house inside or outside, fixing

gutters or floors, repairing leaks or plastering, and replacing broken

window panes. However, repairs made as part of a larger remodeling or

restoration project are treated by the IRS as capital improvements that

increase basis.

Cooperative apartment. Your basis in the apartment is usually the cost of

your stock in the co-op housing corporation, which may include your share of

a mortgage on the apartment building.

Figuring Adjusted Basis

Adjusted basis in your home is cost basis adjusted for items. The Adjusted

Basis of Home Sold Worksheet may be used to figure adjusted basis.

Increases to cost basis include: improvements with a useful life of more

than one year, special assessments for local improvements, and amounts spent

after a casualty to restore damaged property.

Decreases to cost basis include: gain you postponed from the sale of a

previous home before May 7, 1997, deductible casualty losses not covered by

insurance, insurance payments you received or expect to receive for casualty

losses, itemized deductions claimed for general sales taxes on the purchase

of a houseboat or a mobile home, payments you received for granting an

easement or right-of-way, depreciation allowed or allowable if you used your

home for business or rental purposes, any allowable tax credit after 2005

for a home energy improvement that increases the basis of the home,

residential energy credit (generally allowed from 1977 through 1987) claimed

for the cost of energy improvements added to the basis of your home,

adoption credit you claimed for improvements added to the basis of your

home, nontaxable payments from an adoption assistance program of your

employer that you used for improvements added to the basis of your home,

District of Columbia first-time homebuyers credit (allowed to qualifying

first-time homebuyers for purchase after August 4, 1997 and before 2012 ),

and an energy conservation subsidy excluded from your gross income because

you received it (directly or indirectly) from a public utility after 1992 to

buy or install any energy conservation measure. An energy conservation

measure is an installation or modification that is primarily designed either

to reduce consumption of electricity or natural gas or to improve the

management of energy demand for a home.

Planning Reminder

Gains Postponed Under Prior Law Rules

Gain on a previous home sale that you postponed under the prior law rollover

rules reduces the basis of your current home if your current home was a

qualifying replacement residence for the previous home. Postponed gains on

several earlier sales may have to be taken into account under the basis

reduction rule. The basis reduction will increase the gain on the sale of

your current home.

Improvements. Improvements add to the value of your home, prolong its useful

life, or adapt it to new uses. You add the cost of improvements to the basis

of your property.

Examples of improvements include: bedroom, bathroom, deck, garage, porch,

and patio additions, landscaping, paving driveway, walkway, fencing,

retaining wall, sprinkler system, swimming pool, storm windows and doors,

new roof, wiring upgrades, satellite dish, security system, heating system,

central air conditioning, furnace, duct work, central humidifier, filtration

system, septic system, water heater, soft water system, built-in appliances,

kitchen modernization, flooring, wall-to-wall carpeting, attic, walls, and

pipes.

Adjusted basis does not include the cost of any improvements that are no

longer part of the home.

EXAMPLE

You installed wall-to-wall carpeting in your home 15 years ago. In 2017, you

replace that carpeting with new wall-to-wall carpeting. The cost of the new

carpeting increases your basis, but the cost of the old carpeting is no

longer part of adjusted basis.

Recordkeeping. Ordinarily, you must keep records for three years after the

due date for filing your return for the tax year in which you sold your

home. But you should keep home records as long as they are needed for tax

purposes to prove adjusted basis. These include: (1) proof of the home’s

purchase price and purchase expenses, (2) receipts and other records for all

improvements, additions, and other items that affect the home’s adjusted

basis, (3) any worksheets you used to figure the adjusted basis of the home

you sold, the gain or loss on the sale, the exclusion, and the taxable gain,

and (4) any Form 2119 that you filed to postpone gain from a home sale

before May 7, 1997.

Personal and Business Use of a Home

If in 2017 you sold a home that was used for business or rental as well as

residential purposes, you may be able to exclude part or all of any gain

realized on the sale. The excludable amount depends on whether the

non-residential and residential areas were part of the same dwelling unit,

whether the ownership and use tests were met, whether depreciation

was allowable after May 6, 1997, and whether the non-residential use was

before 2009 or after 2008.

Nonqualified use after 2008. Gain allocable to periods of “nonqualified” use

(not used as principal residence) after 2008 is not excludable from income, but certain nonresidential periods are excluded from the definition

of nonqualified use. For example, renting your home after you (and your

spouse) move out is not nonqualified use if the rental occurs within the

five-year period ending on the date of sale.

Law Alert

Nonqualified Use After 2008 May Limit Exclusion

Unless an exception applies, any period after 2008 that a home is not

used as your principal residence is considered a period of “nonqualified

use,” and gain allocable to the nonqualified use is taxable, even if the

two-year residential use test for an exclusion is otherwise met.

The IRS does not treat home office use or rental of a spare room after 2008

as nonqualified use.

Home office or rental space within your principal residence. The IRS takes

the position that gain does not have to be allocated between the residential

and business use portions of your home where both are within the same

dwelling unit. This rule allows a home office to be considered part of your

residential property for purposes of the home sale exclusion. Similarly, the

IRS considers renting a spare room as a bed-and-breakfast bedroom to be

residential use. If the two-out-of-five-year ownership and use test

is met for the regular residential portion, you are also treated as meeting

the two-year residential use test for the home office or rental space, even

if you used the area as a business office or rented room for your entire

period of ownership. As a result, the gain on the entire residence is

eligible for the exclusion, except for the gain equal to depreciation for

periods after May 6, 1997. The gain equal to post–May 6, 1997, depreciation

is never excludable; it must be reported on Schedule D (Form 1040) as unrecaptured Section 1250 gain.

EXAMPLE

Alice bought a house in March 2011 that she lived in as her principal

residence. She used one room as a law office from May 2013 until September

2016, and claimed depreciation deductions of $2,500 for the office space

during that period. She sells the home in 2017. Assume that gain on the sale

is $24,000. Since the office and residential area were in the same dwelling

unit, Alice does not have to allocate gain to the office. Since she meets

the ownership and use tests for the residential part, the tests are also

considered met for the office space, She may exclude $21,500 of the $24,000

gain from her 2017 income. The $2,500 of gain equal to depreciation cannot

be excluded. Alice reports her $24,000 gain and the $21,500 exclusion in

Part II of Form 8949. The $2,500 gain attributable to the depreciation

is unrecaptured Section 1250 gain, which Alice enters on the Unrecaptured

Section 1250 Gain Worksheet in the Schedule D instructions.

Depreciation allowed or allowable. Under IRS rules, you must reduce your

basis in the home for purposes of figuring gain on a sale by any

depreciation you were entitled to deduct, even if you did not deduct it.

Furthermore, you cannot exclude the gain equal to the depreciation allowed

or allowable for periods after May 6, 1997. This means that if you were

entitled to take depreciation deductions for periods after May 6, 1997, but

did not do so, the gain equal to the allowable depreciation is generally not

excludable. However, if you have records showing that you claimed less

depreciation than was allowable, the IRS will reduce the excludable gain

only by the claimed (allowed) depreciation.

Business or rental area separate from your dwelling unit. If you sell

property that was partly your home and partly business or rental property

separate from your dwelling unit, and the business/rental use of the

separate part exceeded three years during the five years before the sale,

the gain allocable to the separate part is not eligible for an exclusion

(since the two-year use test has not been met for that part) and must be

reported as taxable income on Form 4797. This could be the case if you lived

in one apartment and rented out other apartments in the same building, you

rented out an unattached garage or building elsewhere on your property, your

apartment was upstairs from your business, you operated a business from a

barn or other structure separate from your business, or your home was

located on a working farm.

No Loss Allowed on Personal Residence

A loss on the sale of your principal residence is not deductible. You do not

have to report the sale on your return unless you received a Form 1099-S. If

you received Form 1099-S, you must report the sale on Form 8949 even

though the loss is not deductible. Code “L” must be entered in column (f) of

Form 8949 to indicate that the loss is not deductible, and the nondeductible

loss must be entered as a positive adjustment in column (g). These are the

same reporting rules as for a second home or vacation home discussed below.

If part of your principal residence was used for business in the year of

sale, treat the sale as if two pieces of property were sold. Report the

personal part on Form 8949 and the business part on Form 4797. A loss is

deductible only on the business part.

Second home or vacation home. If you sell at a loss a second home or

vacation home that was used entirely for personal purposes and the sale was

reported on Form 1099-S, you report the sale on Form 8949 and Schedule D,

even though the loss is not deductible. On Form 8949, report the

proceeds in column (d) and your basis in column (e). The loss (excess of

basis over proceeds) is not deductible, so code “L” must be entered in

column (f) and the amount of the loss entered as a positive amount in column

(g). The positive adjustment in column (g) negates the loss, so the gain or

loss in column (h) will be “0”. If in the year of sale part of the

home was rented out or used for business, allocate the sale between the

personal part and the rental or business part; report the personal part on

Form 8949 and the rental or business part on Form 4797.

Loss on Residence Converted to Rental Property

You are not allowed to deduct a loss on the sale of your personal residence.

If you convert the house from personal use to rental use you may claim a

loss on a sale if the value has declined below the basis fixed for the

residence as rental property.

Filing Tip

Loss Allowed

If you sell a house that has been converted from personal to rental use, and

the sales price is less than the conversion date basis, a loss on the sale

is deductible.

To determine if you have a loss for tax purposes, you need to know the

conversion date basis. This is the lower of (1) your adjusted basis

for the house at the time of conversion or (2) the fair market value at the

time of conversion. Add to the lower amount the cost of capital improvements

made after the conversion, and subtract depreciation and casualty loss

deductions claimed after the conversion. To deduct a loss, you have to be

able to show that this basis exceeds the sales price. For example, if you

paid $200,000 for your home and convert it to rental property when the value

has declined to $150,000, your conversion date basis for the rental property

is $150,000. If the property continues to decline in value, and you sell for

$125,000 after having deducted $10,000 for depreciation, you may claim a

loss of $15,000 ($140,000 (conversion date basis of $150,000 reduced by

$10,000 depreciation) – $125,000 sales price). Your loss deduction will not

reflect the $50,000 loss occurring before the conversion.

Caution

Temporary Rental Before Sale

A rental loss may be barred on a temporary rental before sale. The IRS and

Tax Court held that where a principal residence was rented for several

months while being offered for sale, the rental did not convert the home to

rental property. Deductions for rental expenses were limited to rental

income; no loss could be claimed. A federal appeals court disagreed and

allowed a rental loss deduction.

EXAMPLE

In 1988, Adams bought a house in Fort Worth, Texas. He paid $124,000, put in

capital improvements, and lived there until he was forced to put it on the

market when he lost his job. In 1989, he listed the house with a broker for

$145,000. After receiving no offers, he decided to lease the house through

1990. By October of 1990 Adams owed $4,551 in property taxes and was three

months behind on his mortgage payments. Fearing foreclosure, he sold the

house for $130,000.

For purposes of figuring a loss, Adams assumed that the fair market value at

the time of conversion was equal to the $145,000 list price. The adjusted

basis of the house was $141,026. As this was less than the estimated fair

market value of $145,000, he used the $141,026 adjusted basis to figure a

loss of $11,026 ($130,000 – $141,026). The IRS claimed the fair market value

at the time of conversion was equal to the actual sale price of $130,000.

Since basis for the converted property is the lesser of fair market value

($130,000) or adjusted basis ($141,026), Adams had no loss on the sale.

However, the Tax Court allowed a $5,000 loss by fixing the fair market value

at the time of conversion at $135,000. It held that Adams sold at a lower

price because of his weak financial position of which the buyer took

advantage. The court figured the $135,000 as follows: $129,000 fair market

value in 1988 (based on an appraisal report, which both parties agree was

correct), plus $6,000 of appreciation attributable to the capital

improvements made to the property after it was converted.

Partially rented home. If you rented part of your home for over three years

during the five years preceding the sale, you must allocate the basis and

amount realized between the portion used as your home and the rented portion. A loss on a sale is allowable on the rented portion, which is

reported on Form 4797.

Profit-making purposes. Renting a residence is a changeover from personal to

profit-making purposes. If a house is merely put up for rent such as by

listing it with a realty company but little else is done to obtain tenants

and the property is in fact not rented, the IRS is likely to conclude that

it was not converted to property held for the production of income and a

loss on the sale will be treated as a nondeductible personal loss.

Similarly, where a house is only rented for several months prior to a sale,

the IRS may not treat this as a conversion to rental property and may

disallow a loss deduction claimed on the sale.

Loss allowed on house bought for resale. A loss deduction may also be

allowed where you acquired the house as an investment with the intention of

selling it at a profit, even though you occupied it incidentally as a

residence prior to sale. In an unusual case, an owner bought a house with

the intention of selling it. He lived in it for six years, but during that

period it was for sale. The Tax Court allowed him to deduct the loss on its

sale by proving he lived in it to protect it from vandalism and to keep it

in good condition so that it would attract possible buyers.

In another case, an architect and builder built a house and offered it for

sale through an agent and advertisements. He had a home and no intention to

occupy the new house. On a realtor’s advice, he moved into the house to make

it more saleable. Ten months later, he sold the house at a loss of $4,065

and promptly moved out. The loss was allowed on proof that his main purpose

in building and occupying the house was to realize a profit by a sale; the

residential use was incidental.

Gain on rented residence. You have a gain on the sale of rental property if

you sell for more than your adjusted basis at the time of conversion, plus

subsequent capital improvements, and minus depreciation and casualty loss

deductions. The sale is subject to the rules for depreciable

property.

Loss on Residence Acquired by Gift or Inheritance

You may deduct a loss on the sale of a house received as an inheritance or

gift if you personally did not use it and offered it for sale or rental

immediately or within a few weeks after acquisition.

Planning Reminder

Inherited Residence

If you inherit a residence in which you do not intend to live, it may be

advisable to put it up for rent to allow for an ordinary loss deduction on a

later sale. If you merely try to sell, and you finally do so at a loss, you

are limited to a capital loss.

EXAMPLES

1.

A couple owned a winter vacation home in Florida. When the husband died, his

wife immediately put the house up for sale and never lived in it. It was

sold at a loss. The IRS disallowed her capital loss deduction, claiming it

was personal and nondeductible. The wife argued that her case was no

different from the case of an heir inheriting and selling a home, since at

the death of her husband her interest in the property was increased. The Tax

Court agreed with her reasoning and allowed the capital loss deduction.

2.

A widow inherited a house owned by her late husband and rented out by his

estate. Shortly after getting title to the house, she sold it at a loss that

she deducted as an ordinary loss. The IRS limited her to a capital loss

deduction. The Tax Court agreed. She could not show any business activity.

She did not negotiate the lease with the tenant who was in the house when

she received title. She never arranged any maintenance or repairs for the

building. Moreover, she sold the property shortly after receiving title,

which indicates she viewed the house as investment, not rental, property.

3.

An inherited residence was rented out by the owner to her brother for $500 a

month when the fair market rental value was $700 to $750 per month. When she

sold the residence at a loss, the IRS disallowed the loss, and the Tax Court

agreed. The below-market rental was treated as evidence that she held the

property for personal purposes, not as rental property or as investment

property held for appreciation in value.

|